Larry Ochs: tenor saxophone, Chris Brown: piano, Donald Robinson: drums

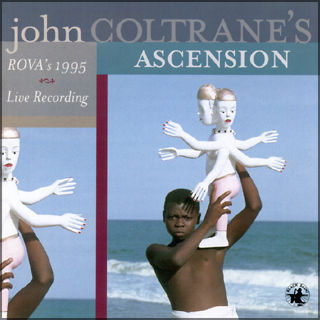

Ascension

(John Coltrane/Jowcol/BMI)

John Raskin and Steve Adams: alto saxophones

Larry Ochs, Bruce Ackley, Glenn Spearman: tenor saxophones

Dave Douglas and Raphe Malik: trumpets

George Cremaschi (left channel) and Lisle Ellis (right channel): basses

Chris Brown: piano

Donald Robinson: drums

1997 - Black Saint (Italy) (CD) Great American Music Hall, San Francisco, CA, December

9, 1995 Bruce Ackley: tenor sax (2); Steve Adams: alto sax (2); Larry Ochs: tenor

sax; Jon Raskin: alto sax (2); Glenn Spearman, tenor sax (2); Dave Douglas trumpet

(2); Raphe Malik, trumpet (2); Chris Brown, keyboards; Lisle Ellis, bass; George

Cremaschi, bass (2); Donald Robinson, drums Solo order of horns on "Ascension":

Spearman, Malik, Adams, Ackley, Ochs, Douglas, Raskin

"What this is a plexus of voices, all of different kinds..."

(A.B. Spellman from the original liner notes to Ascension)

The sonic universe that John Coltrane helped to reveal has become the Terra Firma

of the present-day jazz renegade: a world of fantastic dimensions that still delights

and challenges both practitioners and listeners alike. Rova member Jon Raskin organized

a performance of Coltrane's Ascension to mark the 30th anniversary of the 1965 recording

and to celebrate Trane's largely ignored late period. The piece stands as a model

of collective improvisation that has resonated through the past three decades, providing

a blueprint for late 20th century aural architects. Because of its scale, form,

and intensity, Ascension may be Coltrane's most profound work.

As participant Marion Brown said, "You could use this record to heat up

the apartment on those cold winter days."

The precedent for Ascension was Ornette Coleman's startling Free Jazz, which was

recorded five years earlier. This 1960 ‘Double Quartet' session was revolutionary

in every way and remains a challenge to the jazz mainstream almost 40 years later.

(Current trends don't predict golden anniversary celebrations at Lincoln Center

for either masterpiece.) The Ornette release featured a cover photo of Jackson Pollock's

White Light, a painting of overwhelming power. Abstract expressionist art, or action

painting, with its dynamic surfaces and shifting energy fields, was the visual analog

of Coleman's musical impulse. The musicians of the Free Jazz octet danced with abandon

between foreground and background of the music like colors and shapes exploding

the picture plane. Each was at liberty to join soloists in conversation, taunting

the claustrophobic tradition of solos over a restricted rhythm section. Ornette

had laid siege to accepted practices in jazz that perpetuated a hierarchy of soloist

over ensemble--individual over community.

Archie Shepp said, "The idea is similar to what the action painters do

in that it creates various surfaces of color which push into each other, creates

tensions and counter tensions, and various fields of energy."

With Ascension Coltrane presented a similar forum for improvisers. Like Free Jazz,

Coltrane's extended work features a mid-sized ensemble in a series of solos tied

together by free-blowing tutti passages that are driven by simple motifs and designated

tonal centers. While Coltrane retained remnants of the contemporary jazz environment

by having only the piano, two basses, and drums provide accompaniment for the horn

soloists, the themes of Ascension are charged dynamic vehicles that engage the players

in thick layers of improvised dialogue--a taboo in mainstream jazz. The resultant

network is a plexus of voices striving for transformation and attainment. Soloists

are hurled into the vortex of the music to explore the possibilities of sound. This

is jazz creativity at its most advanced.

As Shepp points out..."The precedent for what John Coltrane did here goes

all the way back to New Orleans, where the voicings were certainly separate but

the group idea held."

In Raskin's arrangement of Ascension, concertmaster Glenn Spearman was called on

to indicate by hand cues which written material was to come next. On a cued downbeat

the orchestra moved to a predetermined theme or tonality. This method (we later

learned that Trane employed the same approach) allowed for a spontaneous reading

of the material, integrating the composed and improvised aspects of the work. The

nature of the preceding solo dictated to Glenn which direction the next ensemble

passage might take; and the spin of that ensemble section impacted the emerging

soloist. For Rova and co-conspirators, directing improvisations as they are unfolding,

by hand cues and other means, is elementary to our m.o. Intuition and a keen sense

of orchestral architecture helped the soloists, ensemble, and concertmaster to shape

an exhilarating rendition of this inspirational composition. Spearman half-joked

that we do it every year in December as a kind of muliticultural Handel's Messiah.

Our evening began with a quartet of Larry Ochs, Chris Brown, Lisle Ellis, and Donald

Robinson in a loosely limned version of Welcome, also included here. Ascension completed

the first set. The second set opened with Dave Douglas' quintet arrangement of Liberia,

continued with a Spearman/Robinson duo of Vigil, followed by Raskin's quartet treatment

of One Down, One Up. We closed the concert with an ensemble improvisation. With

burning enthusiasm, all eleven musicians rose to the occasion, making deeply inspired

contributions. The vibe in the room was electric.

Rova chose collaborators well versed in high-energy group improvisation for the

December 1995 performance: colleagues who are part of a global community of improvisers

transformed by Coltrane's music and his milieu. As the quartet enters its 19th season,

we are proud to set the tone for our next decade with this release. In an era of

jazz with an ever-narrowing perspective, stifled by both industry and academy, we

heartily embrace the humanity of Trane's conception and his commitment to continuous

renewal. We are indebted to John Coltrane for the visionary design of his art and

to the innovators of the Ascension orchestra for their fearless individuality and

cooperative spirit.

"There is never any end. There are always new sounds to imagine: new feelings

to get at. And always, there is a need to keep purifying these feelings and sounds

so that we can really see what we've discovered in its pure state. So that we can

see more clearly what we are. In that way, we can give to those who listen, the

essence -- the best of what we are. But to do that at each stage, we have to keep

on cleaning the mirror. " -- John Coltrane, 1965

-- Bruce Ackley

June, 1996